BLOG

How Hackers Hold Hospitals, and Your Health, for Ransom | WebMD

Published On April 26, 2021

Article by Paul Frysh, WebMD | Medically reviewed by Neha Pathak, MD

Brian Selfridge knew his time was up. From his perch in a locked conference room with the blinds half closed, he could see two members of the hospital IT team rounding the corner with what looked like a clear sense of purpose.

He suppressed a smile as he watched the pair running circles around each other.

One of them -- brow furrowed, eyes buried in an open laptop -- walked right past his room, saying, "He's right here! He's got to be!"

Selfridge knew he was minutes, if not seconds, from being found out. But that was fine. He and his team had hacked into the hospital computer system from a car in the parking lot several days ago. They went in through a cardiac ECG system that was a few years old and so more vulnerable to hacking than newer devices. But there were 10 other ways into the system that would have been just as easy.

In fact, they didn't even need to be on the premises to do a hack like this. A well-crafted "phishing" email is typically all you need to get the ball rolling. An unsuspecting employee clicks on a link inside the email and -- boom! -- you're in. You could send that from anywhere -- say from an office in Moscow, or Tehran, or Pyongyang.

He was only onsite this time because he needed to get in as quickly as possible.

If he'd had the time, Selfridge would have stopped to shake his head. But with the IT team closing in, he bagged his laptop, slipped out a side door, and took off to find his partner, who was waiting for him in a nearby car.

All in all, it had been a successful week. He had been lurking inside the computer system for days, looking for weaknesses. By the time the IT team had finally caught on, it didn't matter.

Even now, after they knew their system had been breached -- knew even that one of the hackers had to be inside the hospital -- they still couldn't stop what was happening.

There had been enough time for Selfridge to figure out what information was unsecured, like medical records, and investigate how it might be possible to lock up the hospital's computer system with ransomware.

Ransomware is software code designed to cut off user access to computer systems. Once deployed, the effects are almost immediate. Doctors and nurses may lose access to patients' appointments, medical histories, lab tests, MRI and X-ray images, and medication information. Recordkeeping may go back to pen and paper, a process that's slower and more prone to errors. Hospitals can even lose access to certain software-based medical equipment.

These disruptions can delay patient care and put lives in danger.

But why go to all this trouble just to mess up a hospital computer system?

"Money," Selfridge says. The "ransom" in ransomware.

Once the computer system is down, cybercriminals typically demand payment -- often in the hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars -- in order for hospitals to regain access.

Savvy hospital administrators are already quite familiar with the scheme, as well as with the ruthless gangs that run many of them: Yes, they will shut down your entire hospital. And no, they don't care how many patients are in the building when they do it.

Once locked up, a screen saver often provides detailed instructions about exactly what has happened, how much money it will cost to "fix" it, and how to pay -- typically in untraceable cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin.

The FBI recommends against paying ransoms to cybercriminals. But with patient care -- and bad publicity -- on the line, many hospitals do it anyway.

If they don't pay, they face weeks or months without the technological tools that drive modern medical care.

And even if they do pay for the decryption keys to unlock their systems, it can take weeks to get systems back up and running.

But none of that was going to happen. At least not this time.

That's because Selfridge doesn't work for a criminal gang of hackers. He works for a health care cybersecurity firm, called Meditology Services, that helps protect hospitals from such attacks.

Soon after he got back to his office, Selfridge called the chief information officer of the hospital and told him, "We've got some work to do."

Patient Safety at Risk

Selfridge and his team simulate these attacks because for many facilities, the threat of ransomware has been all too real.

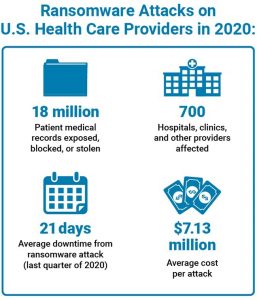

In October 2020, the FBI warned of "increased and imminent cybercrime threat to U.S. hospitals and health care providers" and asked that providers take precautions. But the attacks aren't new. Hospitals, as well as smaller medical practices and outpatient facilities, have been facing ransomware hacks since at least 2016. Cybercriminals deployed ransomware against more than 1,300 U.S. health care facilities over the last 2 years, according to reports in HIPAA Journal.

Still, the issue seems to have reached a turning point. In September 2020, in a widely reported case, a woman in Dusseldorf, Germany, died after a hospital rerouted her to a facility 20 miles away because hackers had shut down their computer systems.

Still, the issue seems to have reached a turning point. In September 2020, in a widely reported case, a woman in Dusseldorf, Germany, died after a hospital rerouted her to a facility 20 miles away because hackers had shut down their computer systems.

For many in the cybersecurity industry, the case was a watershed moment: It was the first public report of a hospital death that may have been a direct result of a ransomware attack. And although some argued the woman might have died even if she'd been admitted sooner, the story highlighted a much broader point that hospital ransomware attacks can take a serious toll on patient care.

"The German case was a single patient at a single hospital that was shut down for a few hours," Selfridge says.

Compare that to the September 2020 attack on Universal Health Services (UHS), with 400 health facilities across the U.S. and the U.K. Their computers were down for weeks after their system was hit with a ransomware attack.

A nurse at a UHS facility in Arizona who was working at the time of the attack said the scene at the facility was "chaotic" and unsafe for patients, especially at first.

Staff had no access to the electronic health records system for close to a month and were unable to use a computerized medication delivery system, said the nurse, who asked that their name not be used for fear of reprisal from their employer.

"The electronic health record, if nothing else, provides a safety net so we're not giving the wrong medications. It's a kind of double check," the nurse said.

Doctors at a UHS acute care center in South Florida, who also spoke on condition of anonymity, said staff had no access to patient records or X-ray files and that medical machinery like fetal heart-rate monitoring systems were down as well.

"Patients were being diverted to other hospitals and people were running around like chickens with their heads cut off," one doctor said.

There were numerous news reports of delays and disruptions, and it was almost a month before UHS put out a press release saying that their systems were back online.

UHS declined to comment to WebMD on the incident, including whether they paid a ransom to the hackers. They did provide an earnings report that describes an "information technology incident" that started Sept. 27, 2020, and caused "disruption to the standard operating procedures at our facilities," and "suspended user access to our information technology applications."

"Certain patient activity, including ambulance traffic and elective/scheduled procedures at our acute care hospitals, were diverted to competitor facilities," according to the report. Other functions, like coding and billing, were delayed into December.

The loss of these kinds of "clinical systems" -- computer hardware and software that controls records, medical devices, medication delivery, scans, and more -- can have real effects on patient health, says M. Eric Johnson, PhD, an expert on health care cybersecurity and dean of Vanderbilt University's Owen Graduate School of Management.

For example, simple medication errors injure and kill thousands of people every year in hospitals across the U.S. Clinical systems help cut down on these and other errors, Johnson says.

This is especially important for emergencies like heart attacks and strokes. Johnson's research with co-author S.J. Choi, PhD, shows that at hospitals where security protocols slowed computer access by just a minute or so, people who came in with a heart attack were more likely to die.

It's certainly not a stretch, Johnson says, to say that delays from a ransomware attack are likely to have more serious effects.

"Anything that slows down medical delivery systems is going to have adverse patient effects."

Some of these effects may be less obvious.

After hackers attacked the University of Vermont Medical Center (UVM) with ransomware in October 2020, the hospital had to delay or cancel some procedures and appointments, including cancer treatments. It was 3 weeks before they had their systems back online.

"Are there adverse reactions to being off of your chemotherapy regimen? You know, I have got to believe that there are," Johnson says.

The data bear this out. One study found a higher risk of death after just a 4-week delay in cancer treatment for seven different cancers. In another study, women with early-stage, triple-negative breast cancer had a higher risk for recurrence and death after a chemotherapy delay of 30 days after surgery.

UVM had better security protocols than many hospital systems. They'd saved backups of their data so they could wipe infected machines clean and restore their files and software without having to pay the cybercriminals. But even so, the shutdown cost UVM about $1.5 million per day in lost revenue and the costs of restoring their computer systems.

They furloughed or reassigned about 300 employees who couldn't do their jobs while the system was down. UVM President and COO Steve Leffler told Vermont news outlets that the final tally of the ransomware attack could be close to $64 million. (UVM did not respond to multiple requests for comment from WebMD.)

It's a good example of why good backups -- copies of essential files -- aren't enough to keep providers safe, says Selfridge from Meditology. "It's not like you just flip a switch," he says.

Individual computers, sometimes thousands of them, may need to be reloaded from the ground up, starting with new operating systems, Selfridge says. That can take lots of time and lots of money.

How Did We Get Here?

Cybercriminals have been hacking into hospital computer systems for 2 decades or more to steal medical records and other personal information to sell on the dark web. This is a breach of patient privacy and a headache for hospitals, especially as they've had to comply with increasingly stringent federal regulations designed to stop it.

Still, that kind of information theft doesn't really affect patient care, says Stoddard Manikin, chief information security officer at Children's Healthcare of Atlanta. That's why many health care providers didn't prioritize cybersecurity as much as they might have.

"It's not always easy to explain to hospital executives why you need to spend millions of dollars to prevent something that you're not sure will happen," he says.

But in the last few years, as cybersecurity experts got better at securing patient information, hackers came up with a much simpler plan: Ransomware.

"It's a much easier payday," Manikin says.

"Say you wanted to break into my house to get at my expensive comic book collection. You have to figure out how to get into my house, how to get from room to room, figure out where it is in the room, and then figure out when you get to the room which comic books are actually valuable. And then you still have to find a buyer."

"Or," says Manikin, "You could just board up my doors, put a guard outside with a gun, and say, 'You can't get back into your own house until you pay me.'"

Since ransomware locks hospitals out of their computer systems instead of stealing from them, cybercrimes against hospitals have evolved from a patient-privacy problem into a much more serious patient-safety problem.

Plus, hospital ransomware attacks emerged so quickly that health care providers found themselves behind in cybersecurity compared to other industries like banks, says Vanderbilt's Johnson.

Banks are more successful at protecting their systems, in part, he says, because they share information among themselves and with federal agencies about how hackers gained access to their systems in live attacks. Then, they work together to formulate shared security protocols, which help prevent attacks and limit damage when they happen. Banks even link their computer systems together so that when one bank is attacked, others on their network know about it almost immediately and can start to protect against it.

But these systems are expensive and take time to develop, test, and implement, Johnson says.

The government helps by setting up information sharing and analysis centers (ISACs) for different industries, including for health care. But, Johnson says, ISACs are only as good as their members.

"Hospitals just aren't nearly as sophisticated, both in terms of their security protocols and in terms of sharing information," Johnson says.

But it's vital for hospitals to share information about ransomware attacks. It's one of the best ways experts and government agencies have to collect the information they need to fight off attacks or stop them before they start, says John Riggi, senior cybersecurity advisor at the American Hospital Association (AHA).

In many cases, it's also the law. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Office of Civil Rights (OCR) requires health care providers to report any attack that exposes or blocks access to the private information of more than 500 people. OCR can investigate hospital records and security practices and levy fines when computer systems are breached.

But, says Riggi, government fines and audits don't exactly encourage information sharing. And hospitals, he says, are too often made into scapegoats in ransomware attacks.

"Look, if we all agree it's not a matter of if but when an organization becomes a victim of a cyber attack -- and no organization is 100% 'breach-proof,' including the federal government, as we've seen -- why is it that when a breach occurs, the victim (a hospital) suddenly becomes the negligent one?"

If you want health care providers to share information more freely with the government and other agencies after an attack, he says, don't punish them as a result of that sharing.

To that end, Riggi spoke before Congress on behalf of the AHA in support of a law, passed in January, that requires the government to shorten audits and reduce fines when hospitals have used "recognized security practices" for at least a year.

"We're certainly not excusing gross negligence," Riggi says. "But where all reasonable efforts have been made to protect the organization from cyber threats, regulators need to consider that no organization is 100% safe."

What Can Be Done?

Law enforcement can help hospital systems navigate an active attack to keep the damage to a minimum. They can help with security protocols to prevent future attacks. Some federal intelligence agencies can even run counterattacks to discourage rogue nations from allowing ransomware hackers to operate with impunity. What they often can't do, Selfridge says, is stop the bad guys from attacking in the first place.

"The FBI knows exactly who these folks are," Selfridge says. "The problem is that they operate in the shadows -- in foreign countries like Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran -- where the FBI and the U.S. government have no authority."

"There are unfortunately too few instances of foreign attackers being caught and prosecuted," he says. That's part of the reason that the rate of attacks is going up so quickly.

"Our only hope of prosecuting foreign attackers is to build bridges with the governments of the countries where they work," Selfridge says.

"I think that's one of the only levers we have, and it's not a great one."

As a result, there's a growing level of brazenness to these attacks that is disconcerting.

In fact, ransomware attacks, particularly on hospitals, have become so easy that wannabe cybercriminals can buy ready-made ransomware kits from the dark web. Some of these kits even provide a help desk, with English-speaking attendants to assist the criminals and, in some cases, the victims as well.

Back at the hospital where IT staff had chased Selfridge off the premises, he and his team got to work. They spent many months helping the hospital implement a plan to build up the systems and protocols to protect against the next intrusion.

It's not flashy work. It's grinding. Vigilance is the most important ingredient. "You could stop 90% of current attacks if you could simply stop people from clicking on links in emails that they don't recognize," Selfridge says. But even if you could do that, he says, hackers would find some other way into your system.

A year later, when the same hospital hired Selfridge and his team to test their cybersecurity again, there was never a question as to whether they would be able to hack into the system. That was a given. The only question was how long it would take to get caught after they were in.

"The results were good," Selfridge says. "We were in for no more than a few hours before they figured out we were there and cut us off." They had good backups, and in a real-world situation, the damage to their systems would have been minimal, he says.

But in the industry as a whole, Selfridge says, there is quite a mountain to climb: The flood of attacks is intense, the consequences for cybercriminals are few, and the risk to hospitals and patients is high. Plus, there's a massive backlog of cybersecurity job openings -- 3.5 million in 2020, according to a report from Cybersecurity Ventures.

Selfridge and other experts see the recent uptick in attacks on health providers as the tip of a much bigger iceberg.

"Powerful entities, including in some cases government agencies, have the power to do far more serious damage than we have seen," he says.

Israeli cybersecurity researchers recently managed to trick doctors with malware that changed information from MRIs and CT scans. They were able to remove cancerous growths from some images and add them to others. Many doctors could not tell the difference.

In theory, experts say, hackers could gain control of any computer-operated system in the hospital.

"There is a real sense that the massive ransomware attacks of the last few months have been a call to arms for the whole industry," Selfridge says.

"I hope, for all our sakes, that we are able to meet the challenge."

Read the full article at WebMD.com

[WEBINAR REPLAY] Your Health Held Hostage: What Ransomware Means for PatientsMeditology hosted a webinar to discuss key themes from the WebMD article above, including trends in ransomware attacks and their direct impact to patients. The session included updates about:

WATCH THE REPLAY HERE |

SOURCES

Brian Selfridge, partner, Meditology Services, Philadelphia.

M. Eric Johnson, PhD, dean, Vanderbilt University Owen Graduate School of Management.

Stoddard Manikin, director of information systems security, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta.

John Riggi, senior cybersecurity advisor, American Hospital Association.

BreastCancer.org: “Delaying Chemotherapy More Than 30 Days Linked to Worse Outcomes for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer.”

British Medical Journal: “Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis.”

Data Breach Today: “Lawsuits After Ransomware Incidents: The Trend Continues.”

Emsisoft Malware Lab: “The State of Ransomware in the US: Report and Statistics 2019,” “The State of Ransomware in the US: Report and Statistics 2020.”

National Law Review: “First Reported Death Connected to Misfired Ransomware Attack on German Hospital.”

Institute of Medicine. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, National Academies Press, 2000.

Security Boulevard: “On That Dusseldorf Hospital Ransomware Attack and the Resultant Death.”

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services: “Health Insurer Pays $5.1 Million to Settle Data Breach Affecting Over 9.3 Million People,” “Submitting Notice of a Breach to the Secretary,” “FACT SHEET: Ransomware and HIPAA.”